From Sudan to Spokane: After nearly 20 years of helping others, interpreter finds refuge in America

The attack on his village was a calculated horror. The attackers knew the village, knew its weakness: the dry, grass-thatched roofs could turn a house into a fiery pyre instantaneously

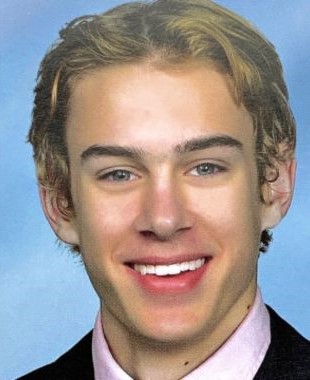

Keri Bambock

World Relief

Hassan remembers the tourists, a brief, vibrant intrusion into his childhood in Sudan. They wandered around the market, peering at the wares and interviewing the locals. They even took a picture with Hassan’s mother, all the while babbling in a strange language. The shopkeeper’s simple explanation: “Those are from very far place. Those are from US.” Taken with the strange people, Hassan thought to himself, “I have to see the place called US.”

But what was the language that the people spoke? English? Hassan would learn English. At school it was required for the students to learn basic English, but most didn’t retain it past the brief lessons. Hassan threw himself into each word, asking for private lessons, driven by a desire he couldn’t yet articulate. A desire that would shape his future as an IOM interpreter.

The attack on his village was a calculated horror. The attackers knew the village, knew its weakness: the dry, grass-thatched roofs could turn a house into a fiery pyre instantaneously. They started by burning the houses. Hassan remembered seeing the flames shoot into the sky. The villagers ran, their desperate flight a tragic mistake. The attackers shot the escapees and forced several back into the fiery homes.

Miraculously, Hassan survived the village attack, escaping to Al Geneina. For nearly two decades, he lived in a state of precarious limbo, building houses to pay his way to Kenya. It was in a Kenyan refugee camp that he met his wife and started his family. Despite the challenging circumstances, Hassan’s determination to learn English never wavered.

During this time, he diligently learned English, adding it to his already impressive linguistic repertoire: Sudanese, Masalit, Swahili, and Arabic.

Hassan was convinced that he didn’t pass the interview – he had applied to be an interpreter for U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). For refugees facing the intense scrutiny of the vetting process, this role was a lifeline, a bridge across language and understanding. The call, when it came, was a shock, a wave of relief washing over him. He’d been chosen to be an interpreter!

Hassan spent years as a USCIS and IOM interpreter, a vital role in conveying the often-heartbreaking narratives of Sudanese refugee families. He told their accounts of fleeing danger, ensuring no detail was lost in each word. Afterwards Hassan would sign a confidentiality agreement: everything that was communicated was interpreted exactly as said.

But the gratefulness of the families followed him out. After the interviews Hassan would often hear words like “thank you for your services.”

“I tell them, that is my job. I have to do that… I’m there for you to make you understand exactly what [the IOM interviewer] says and able to tell your story. That is my job.”